Standart

Imperial yacht

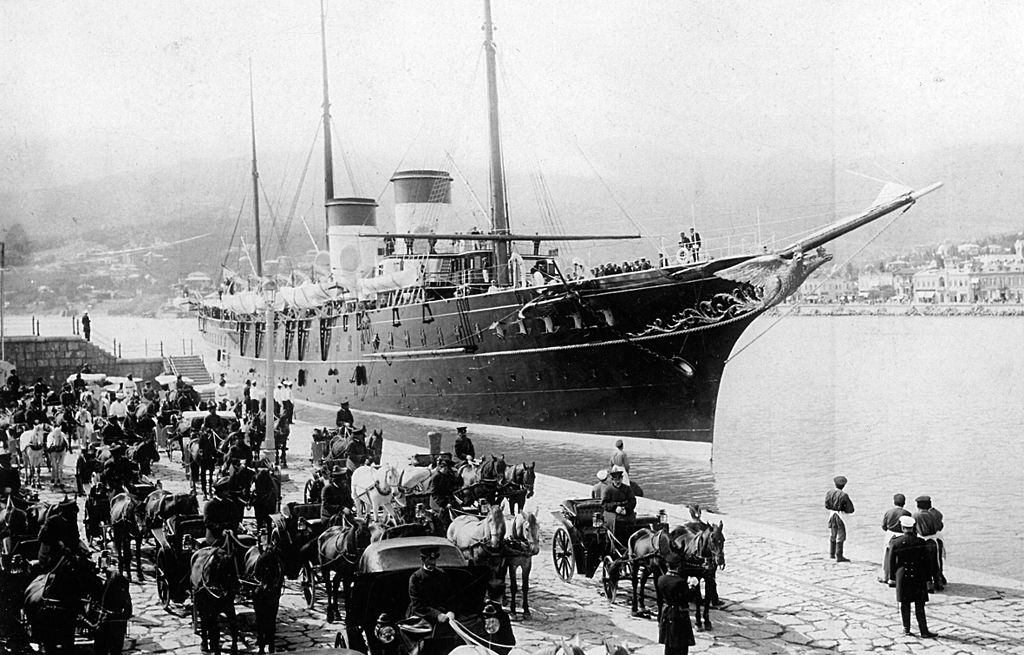

The Imperial Yacht Standart (Штандартъ) was built by order of Emperor Alexander III of Russia. It was constructed at the Danish shipyard of Burmeister & Wain in Copenhagen, in the beginning of 1893. Standart was probably the most exclusive and magnificent yacht ever built. She was launched on 21 March 1895 and came into service early September 1896. Standart was fitted out with ornate trimmings, including mahogany paneling, crystal chandeliers, and equipment that made the vessel a suitable floating palace for the Russian Imperial Family. The ship was manned and operated by a crew from the Russian Imperial Navy. During the reign of Nicholas II, Standart was commanded by a naval Captain, although the official commander was a Rear Admiral, who personally attended the Imperial family. Thecommander in 1914 was Nikolai Pavlovich Sablin. The yacht was used as a veritable floating palace both at official state-business and for private vacations and travel. In June 1908, King Edward VII and Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia met in the Bay of Reval, now Tallinn, the state-banquet was held onboard. The Russian Imperial Family was on vacation on the Standart during the summer of 1914. Here they received news of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo. With the outbreak of World War I, Standart was placed in drydock. After the fall of the Romanov Dynasty, Standart was stripped down and went into naval service and only scrapped as late as 1963. (Top illustration: Russian imperial yacht Standart in Yalta, 1917. Wiki, Public Domain)

On October first, 1893 Emperor Alexander III, the Empress Maria Feodorovna and Tsarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich (the future Emperor Nicholas II) were present at the keel-laying ceremony of building no.183 at Copenhagen where Alexander III personally nailed the first rivet in the keel. When construction advanced, the Emperor made the decision that the ship should be built as a yacht. All construction work was immediately stopped and the ship had to be completely redesigned; the six-month period of practically no construction activity drove the shipyard almost into bankruptcy. In November that same year, a supplementary contract between Burmeister and Wain and the Imperial Russian Navy was issued by the Chief of the Head Office of Shipbuilding and Outfit and for the first time the name of the new vessel, Standart, was mentioned. The Imperial Navy mobilized a visit to Copenhagen to supervise the engineering and construction activities on the new Imperial Yacht; senior constructor (and prince) N.V. Dolgorukov, captain V.V. Friedrichs and some officers closely monitored the ships construction until final completion.

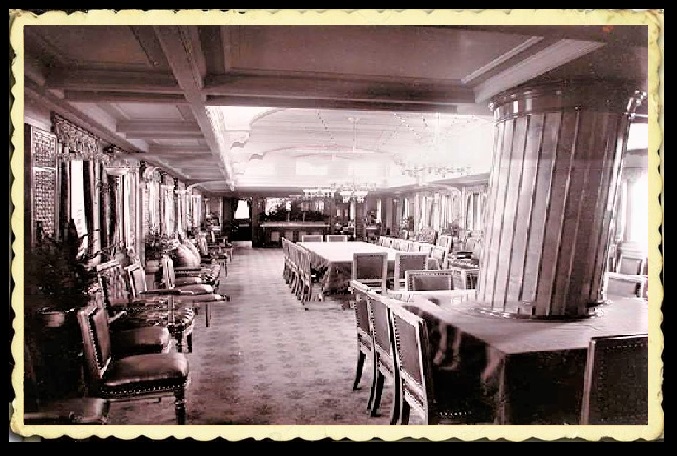

With a length 112 meters, a width of 15,8 meter and a deepgoing 6 meters, the imperial vessel was also a marvel of engineering: A twin screw vessel built of steel with 24 water-tube boilers and a hull divided into sections with a large number of watertight compartments. To prevent and reduce rolling in high sea, large keels were fitted nearly half the length of the ship. The masts were made of steel and Oregon pine. The Imperial apartments were situated on the main deck: Rooms for the Emperor and Empress as well as for the Dowager Empress, each comprising a sitting room, a bedroom and a bath-room. Adjacent to these rooms were the Imperial drawing- and dining rooms. Staterooms for the officers were situated on both sides of the boiler room and the Imperial kitchen was situated between the two funnels. On the lower deck there were rooms for the Imperial children and the Imperial suite. The ship was lighted by electricity; about 1070 lamps being fixed in the various apartments, rooms and corridors. The most costly woods had been used for interior fittings: Imperial suites with solid cherry; for the Empress-Dowager’s suites and Grand Duke’s apartments, birchwood. An elaborate system of copper piping, tinned inside, supplied all areas of the ship with fresh water. Besides the fresh water system, a salt-water system supplied the baths, wash rooms and toilets. Heating of the ship was arranged through hot-water boilers.

The huge vessel docking in Copenhagen, photographed by Peter Elfelt. © KB/Royal Library, Creative Commons.

B & W – the Danish shipyard and industrial company founded in 1846. © KB/Royal Library, Creative Commons.

Burmeister & Wain was a large established Danish shipyard and leading diesel engine producer headquartered in Copenhagen, Denmark. Founded by two Danes and an Englishman, its earliest roots stretches back to 1846. Hans Heinrich Baumgarten (1806–1875) was from the town of Halstenbek near Pinneberg, in the Duchy of Holstein, an area of Germany that was then under the rule of the king of Denmark. He was apprenticed as a coffin maker by a farmer whose livestock he cared for. Later he was a carpenter before becoming a machine minder at the Danish newspaper Berlingske Tidende, whose printing office he later worked for in Berlin. In 1843 he was granted a Danish Royal Charter and what would later become Burmeister & Wain was launched with the opening of a small mechanical workshop in Copenhagen. Carl Christian Burmeister (1821–1898) was son of a cook and restaurant keeper, and studied at the Polytechnical Institute in Copenhagen from 1836–1846. He had been awarded a scholarship abroad after recommendation following an assistantship to the famous scientist Hans Christian Ørsted (1777–1851) who was director there at the time. Burmeister joined the H.H. Baumgarten Company in 1846. They entered into partnership with the opening of the engineering works factory, and was renamed B&B. With Baumgarten as a co-owner, in 1865, William Wain (1819–1882) joined what then became B&W. In 1872 the company became A/S B&W, a limited liability corporation. That same year saw the founding of the Refshale Island shipyard. At this point, Baumgarten, as the first founder, became a director of the board of what he would became Burmeister & Wain Engineering and Shipbuilding in 1880. Wain, from Bolton, England had apprenticed as an engineer in his youth and come up through the trades. He had worked for the Royal Danish Navy and the Royal Dutch dockyards. He came to have several designs to his credit within the company and his ingenuity was seen as “instrumental” in establishing its reputation. Over its 150 years of history, the company grew successfully. B&W became MAN B&W Diesel A/S, part of MAN B&W Diesel Group, a subsidiary of the German corporation MAN AG, with operations worldwide.